540 years after his death at the Battle of Bosworth, it’s still difficult to think of an English King more divisive than Richard III, which makes it very hard to fully uncover the truth about him. Was he the twisted, hunchbacked, scheming murderer of Shakespeare’s history plays? Or was he gentler, misunderstood and much maligned, the victim of Tudor propaganda?

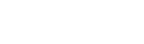

Richard was the last king in a dynasty that lasted more than 300 years. He took the throne at a difficult time, with the country already embroiled in a civil war, as two branches of the royal family (The House of York and the House of Lancaster) battled for control.

The country was still unsettled from years of fighting when Richard’s brother King Edward IV died in 1483. King Edward’s son, also named Edward, was next in line for the throne, but at only 12-years-old he was too young to take full responsibility for a whole country.

Parliament appointed Richard as Lord Protector to help and guide the young Edward V in the early years of his reign.

Before Edward’s coronation, however, there were doubts cast upon Edward IV’s marriage, and whether either of his two sons were actually legitimate. After a brief debate, Parliament declared them both illegitimate and therefore ineligible for the crown, and Richard was crowned king in his nephew’s place.

Prince Edward and his younger brother (confusingly, also named Richard) were taken to the Tower of London, ostensibly for their own protection, but they were never seen again. What happened to the princes in the tower has become one of history’s great mysteries, and cast a dark shadow over the reign of Richard III.

In the end, Richard’s short reign lasted just over 2 years, and his defeat at the Battle of Bosworth Field heralded both the end of the Plantagenet dynasty and the beginning of the Tudors. He was buried unceremoniously in the choir of Greyfriars church in Leicester, but when Henry VIII broke from the catholic church and dissolved the monasteries of England just over 50 years later, the church was destroyed and Richard’s grave was lost.

…Until, that is, a very dedicated team made up of people from the University of Leicester, Leicester City Council, and the Richard III Society applied for permission to dig up what was now a Leicester Council owned car park in 2012.

There was evidence that the church had been located in a particular area of modern Leicester, and they narrowed down the search for Grey Friars church to underneath the Social Services building, its car park, and a playground nearby.

The archeological team planned several trenches, and broke ground on the 25th of August. On the very first day, the very first find underneath the car park (other than brick and concrete wall footings from the previous hundred years) was a human leg bone, followed shortly by a second. While this was exciting for day one, a grave wasn’t an entirely unexpected find - they were looking for a church after all, and there had been a graveyard within the grounds.

Further excavation found that the individual appeared to have been buried swiftly and without much care. The grave was rough. There was no coffin, and based upon the position of the bones there may not even have been a shroud.

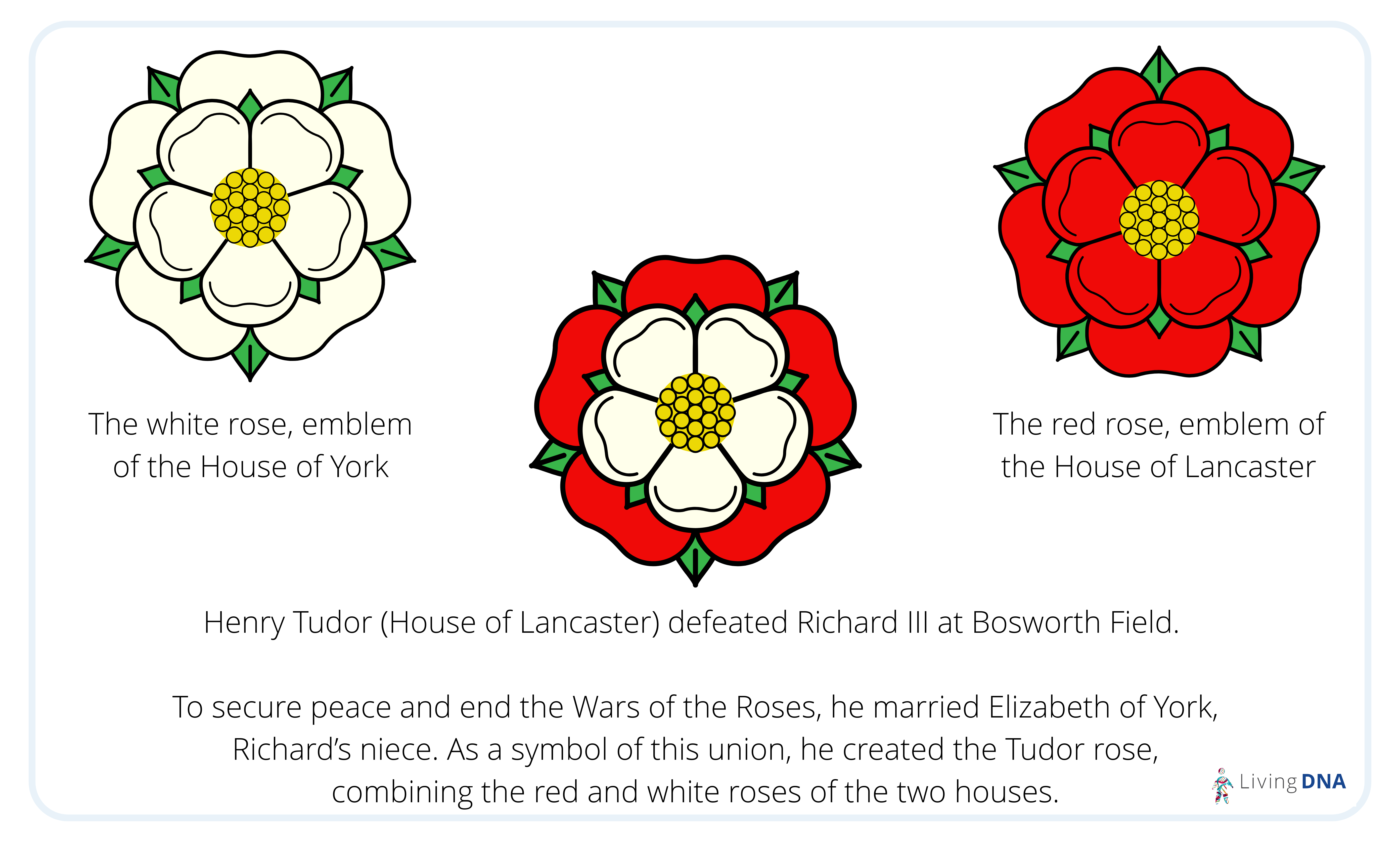

Importantly for the archaeologists, as they carefully uncovered the remains, they found that this individual had a marked curvature of the spine - a condition called scoliosis which Richard III was rumoured to have had, and which Shakespeare exaggerated in his play.

Later examination showed that the individual was male, and had 11 wounds to his body deep enough to have affected his skeleton. He had died a very violent death, in line with Richard’s death in battle.

The real test for the remains would be DNA, and luckily, they were able to extract it. They further confirmed that this was a male, and were even able to identify both his mitochondrial and his Y haplogroups.

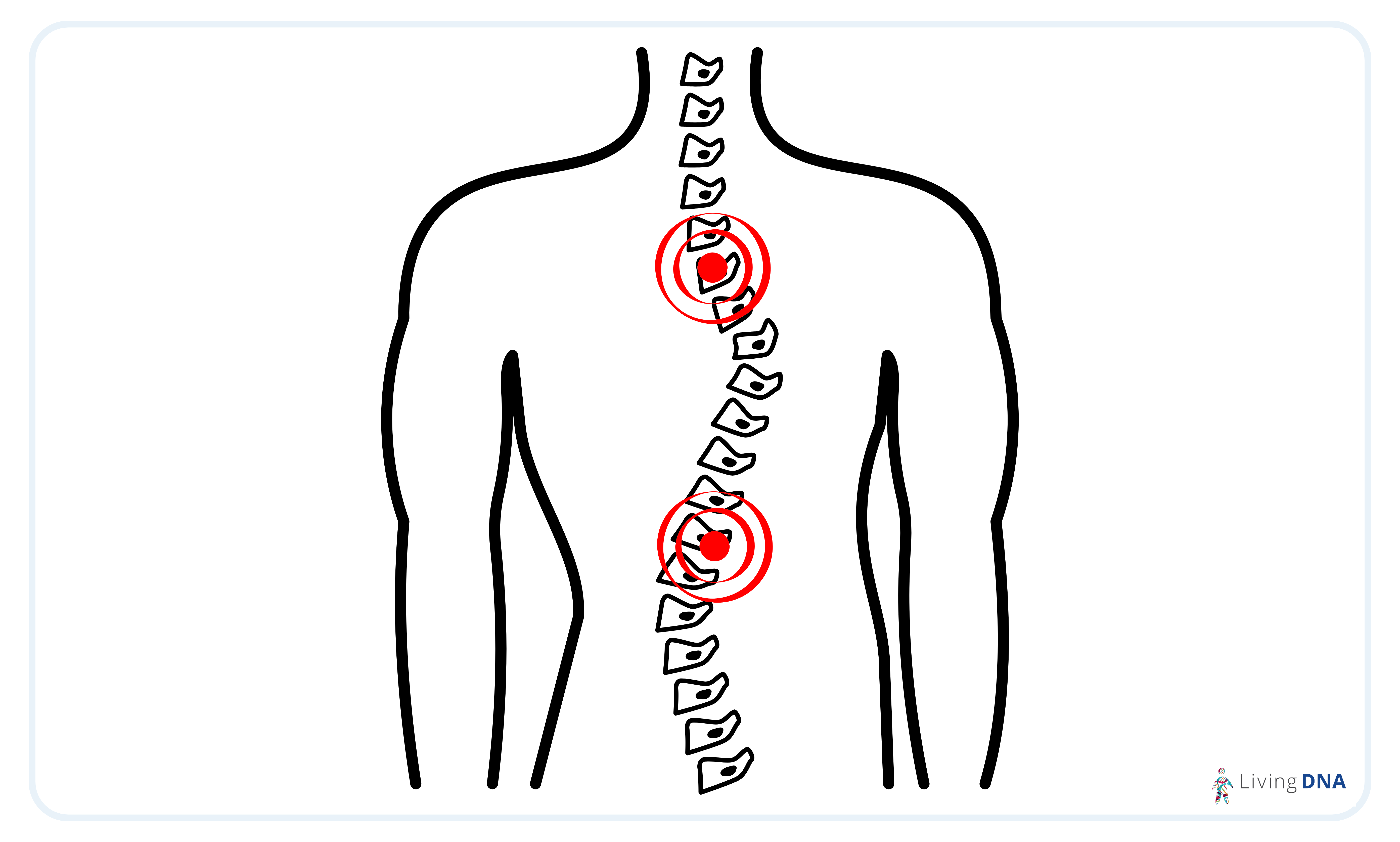

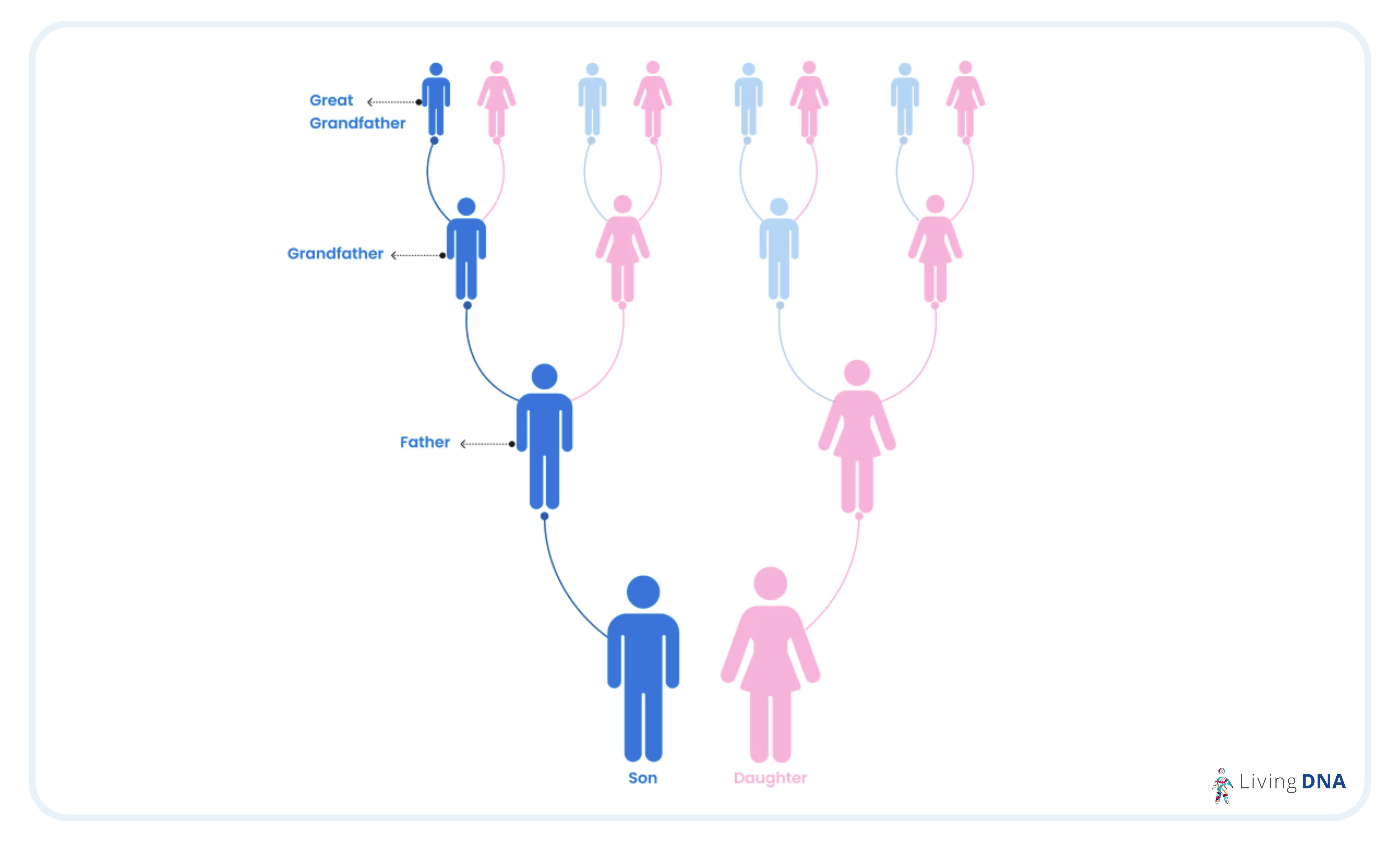

If you’ve taken a test with Living DNA, you have seen your motherline and (if you have a Y chromosome) your fatherline results. These special, tiny pieces of DNA are passed down from mother to all of her children, and from father to his sons. Because of the way haplogroups work, being passed down almost unchanged through the generations, the team at the University of Leicester were able to track down living descendants of Richard’s close relatives (sadly his own sons died without children) to compare them with.

In order to find a person who shared his motherline (mtDNA haplogroup), researchers had to go back up his family tree to Lady Cecily Neville (his mother), then down through his sister Anne of York. They found an unbroken line of mothers and daughters, ending with a Mrs Joy Ibsen. Sadly she had passed away a few years earlier, but her son Michael (who would share the same mitochondrial DNA as his mother but would not be able to pass it on to his own children) agreed to take a test.

Both the remains found under the car park in Leicester and Michael Ibsen shared mtDNA haplogroup J1c2c3.

The Y-DNA haplogroup, Richard’s fatherline, proved to be more contentious. Although an unbroken male line was found in the genealogical record, there wasn’t a genetic match. This means that somewhere in the centuries since Richard lived there was a break in the male line, which isn’t unusual in family trees that stretch back over many generations. Richard’s Y-DNA haplogroup was G2.

Each of these haplogroups survive in more people than just Richard’s direct relatives today. In fact, there are Living DNA customers who share them!

The G2 fatherline is relatively broad, and it has several branches that spring from it. Including all of these branches, there are a whopping 2,432 men who have tested with Living DNA, who all share this link to the past.

The motherline J1c2c3 is far more rare. In fact there are only three people who have ever tested with Living DNA who share this haplogroup, showing a shared common ancestor with Richard III.

History is still divided on Richard III’s character. Tudor portrayals and Shakespeare’s plays show him as a hunchbacked usurper and villain. Revisionists intent on rehabilitating his image, known as Ricardians, see him as a capable ruler who promoted justice and was loyal to his allies.

Richard III’s skeleton and DNA confirmed his identity, his scoliosis, and his violent death on Bosworth Field. It linked him with modern people alive today, and can show us migration routes for his more ancient ancestors. What it can’t do for us, is be a detective in Richard’s story or a witness to his character. We’ll likely never know what happened to the young princes in the Tower of London or how personally involved in their fate Richard was. That part of his story lies beyond the reach of modern science. Richard’s rediscovery does stand as a reminder that each and every one of us carries fragments of the past, handed down to us through our ancestors, the stories written in our DNA.